Turn on the tennis this week, and you’ll probably notice one thing: the court color has changed.

Gone is the red dirt of Roland-Garros; instead, it’s the finely cropped grasses of Europe on display now. But hang on, weren’t the courts blue and bouncy just a few months ago? And why are matches starting in the middle of the night all of a sudden?

The beauty of the tennis calendar is the ATP and WTA Tours are constantly moving around the world, iterating between different surfaces. This can be hard to keep track of, but when you’ve got a good handle on how the tennis season flows, it can enrich the sport even more.

That’s why we’ve put together a straightforward guide on everything you need to know about the tennis calendar.

If it’s the nitty gritty details of event names and dates that you’re after, head to each Tour’s official websites. But if it’s an understanding of what makes each part of the calendar unique, why players choose to play certain events, and what to expect from the rest of the season, then you’re in the right place.

Fast start Down Under

The tennis calendar gets underway with a hiss and a roar in the very first week of the year.

With the first Grand Slam taking place just two weeks into January, this first chunk of the season is all about hitting the courts in Melbourne in optimal shape.

For some players, this looks like playing back-to-back events in order to arrive at the Australian Open full of confidence. They have plenty of options, with a handful of smaller tournaments happening across Australia and New Zealand.

For others, they’ll opt to have an extended off-season, and play their first event of the year in Australia.

The latter half of January is of course then consumed by the year’s first major. Because of how close to the off-season the Australian Open is, it gives a fascinating early look at who’s made big changes, and who’s managed to carry over form from the previous year.

Post-Australian Open wilderness

Following the Australian Open, we have one of two strange little patches in the tennis calendar.

Most big names opt to take the better part of a month off. Either they will have just made a deep run and be looking to celebrate and recover, or, they will have suffered disappointment and be looking to make some tweaks.

Either way, February is something of a wilderness in tennis. There’s plenty going on, but winning a title at this stage of the season always comes with something of an asterisk to it.

Those who do continue playing immediately post-Australian Open have two broad options: stay on hard courts, or hit the clay.

For hard courts, there are a handful of smaller tournaments in both the US and Europe. These lead into the Middle Eastern hard court swing. This happens for both Tours, but is notably bigger for the WTA Tour, with multiple WTA 1000 tournaments.

The Golden Swing

Those that hit the clay will head to what’s known as ‘the Golden Swing’ in South America. This is just for the men, sorry ladies, and sees the ATP Tour hit Argentina and Brazil for three weeks of clay court action.

What players do here largely depends on their priorities. Lower ranked players will be eager to make the most of weaker draws and pick up some valuable points to boost their ranking, while those who are secure in their position will look to rest ahead of the next chunk of the season.

Where players are from usually influences whether they head to Europe, North America or South America too–typically, they’ll play whichever tournaments are closest to home at this stage of the year.

The Sunshine Double

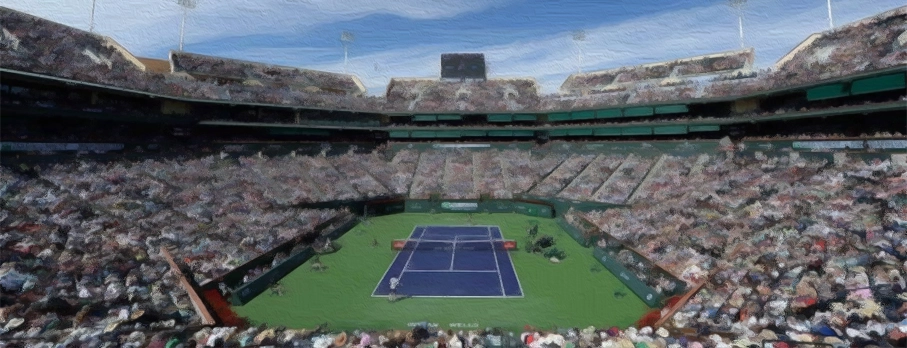

Having diverged in February, March sees the best of the best reconvene for a month of tennis in the United States.

This sees two back-to-back 12-day long Masters 1000 tournaments unfold across Indian Wells and Miami. Known as ‘the Sunshine Double’, these two events are as big as it gets outside of the Grand Slams and Tour Finals. Anyone that’s not injured will be present.

European clay swing ahead of Roland-Garros

Immediately after a month of hard courts in America, both Tours head to Europe and hit the dirt.

This begins the long road to Roland-Garros, known as the European clay swing. While it varies between the ATP and WTA Tours, this chunk of the calendar sees several 1000-level tournaments, plus plenty of 250s and 500s as well.

For the men, the clay season kicks off officially in Monte-Carlo for a Masters 1000. A few players may have already played the week beforehand, either in Europe or in a few US clay events. However, this is where most get their first taste of clay–and it often brings a good number of upsets given the change in surface.

Then it’s bang, bang, bang. From Monte-Carlo, the Tour hits Barcelona, Madrid, Rome and ultimately Paris for Roland-Garros, the year’s second Grand Slam.

Of course there are other smaller tournaments sprinkled in, but ultimately, the goal of April and May is to be peaking on clay courts when the French Open begins in late May.

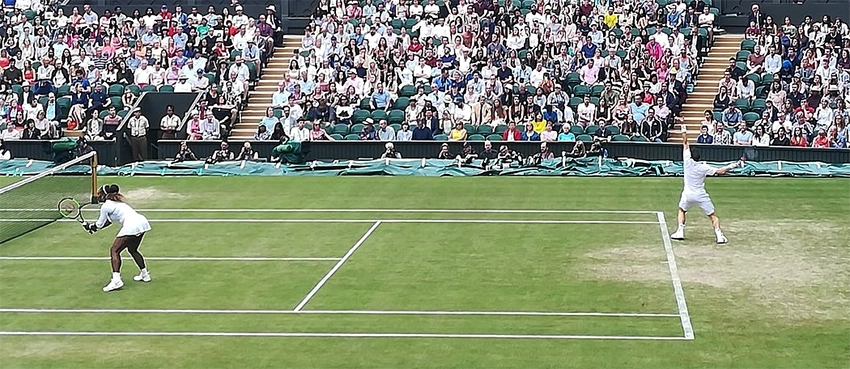

Straight onto grass for Wimbledon

In one of the most packed sections of the tennis calendar, players head straight from the clay of Paris to the pristine grass of elsewhere in Europe.

Why? Because the year’s third Grand Slam, Wimbledon, is kicking off in three weeks, and it’s on a completely different surface.

This period of the season is a cross between pre-Australian Open, and the European clay court swing. On the one hand, players are trying to arrive in London for Wimbledon in the best shape possible, so might opt not to play any warm ups. On the other, there’s a new surface to adapt to, so playing as many events as possible is advantageous.

Usually, players take very different approaches. Someone like Iga Swiatek or Casper Ruud heads home and relaxes for a few weeks, then arrives at Wimbledon to play grass for the first time. Others, like Andy Murray or Matteo Berrettini, will be targeting this as their big opportunity, and getting as much practice as possible in.

Post-Wimbledon (the Ruud swing)

Speaking of Ruud, following Wimbledon there is another strange patch in the tennis calendar.

Most top players will elect to take a break and rest at this stage of the season. Others, like Ruud, will head back onto clay for a handful of small tournaments across Europe.

It’s a strange move. There’s no real reason to play clay, with no big tournaments to prepare for. But, players who love clay, and perhaps didn’t have the most active grass season, will still dive into this chunk of the calendar with vigor.

Back to the States for hard courts

Following the post-Wimbledon weirdness, both Tours then head back to the United States for a good swatch of hard court action.

This is all in aid of preparing for the US Open in late August. However, there are points to be had in the pre-US Open hard court swing, with a handful of 500- and 1000-level tournaments on offer.

These usually attract a full draw of players, with everyone eager to pick up points and boost their seeding heading into the year’s final Grand Slam.

Asian and indoor hard court swings

Following the US Open, the tennis season begins to unravel a little.

Technically there are two sections of the tennis calendar remaining–the Asian hard court swing, and the indoor hard court swing–but we’ve lumped them together for a reason.

Once the Grand Slams have finished for the year, things begin to change. Often, top players will already have qualified for the year-end championships, and will be looking to manage their energy. Others will be injured, or fatigued.

This gives rise to another section of the calendar similar to February, where some players can get on hot streaks and experience disproportionate success. We saw it with Holger Rune and Felix Auger-Alliassime recently, where both picked up a large swath of points in October.

Draws may be weaker, upsets occur more easily, and some players get on runs. Those who haven’t qualified for the year-end finals will be desperately trying to make up points, and might be packing in tight schedules as a result.

It’s a fascinating, if not a little bizarre section of the year.

Finals and Davis Cup

The season ends with finals for both the men and women, where the top eight points scorers across the calendar year compete for a title.

This is the next closest thing to a Grand Slam with a potential 1500 points on offer and great prize money, albeit in a very different format. It’s great watching, and often has the year-end No 1 spot on the line too.

For players under the age of 21, they have their own ‘Next Gen’ finals as well.

Finally, the Davis Cup team event will have its finals in November as well, and is usually one of the final events in the tennis calendar.

So, next time you notice the tennis court changing color, or broadcast times switching suddenly, you’ll now know why, and the significance of the change as well.