James Lloyd is back with part 2 of his series “A Head of the Game”. This time he talks about the father of the modern tennis racquet.

Read part 1 of James’ series here called A Head of the Game – Game-changers. James was also featured in a video about modern vs classical racquets on YouTube.

Papa’s got a brand-new bat (the father of the modern tennis racquet).

Nonsense!!!! I hear you shout. How is the Prince Original Graphite Oversize the father of the ‘modern’ tennis racket?

Well, it is ‘just a racket’, I agree. Bloody good one, though. I still have one lying around, a later version. I won’t give chapter and verse on static weights, swing weights, twist weights, balance points, and beam widths. That is a Tennisnerd’s role, and he knows far more than I, as no doubt do some of you.

The way a frame is made, the woven pieces of carbon fibre or aramid fibre or whatever exciting new material is interwoven or applied, the ‘lay-up’, has not just millions, but infinite possible combinations or ‘recipes’ for creating a finished product. It is a bit like a food dish, in that you can freely choose what to put in and how much of whatever to put in, and how long to bake it for and at the end people either like it or they don’t, you may create something amazing but you are constantly discovering new ingredients or being inspired by others. You can try to emulate or copy, try to ‘better’ it.

The amount of trial and error, attempts at perfection and the sweat and tears is truly mind-boggling, especially when you consider you always have rivals trying to better, or copy, or match your design. It makes you mindful of why ‘mammas secret ingredient’ is…. secret. How anyone ever settled on any finished product is astounding. Especially when the future of your brand, your business, your employees is always at stake.

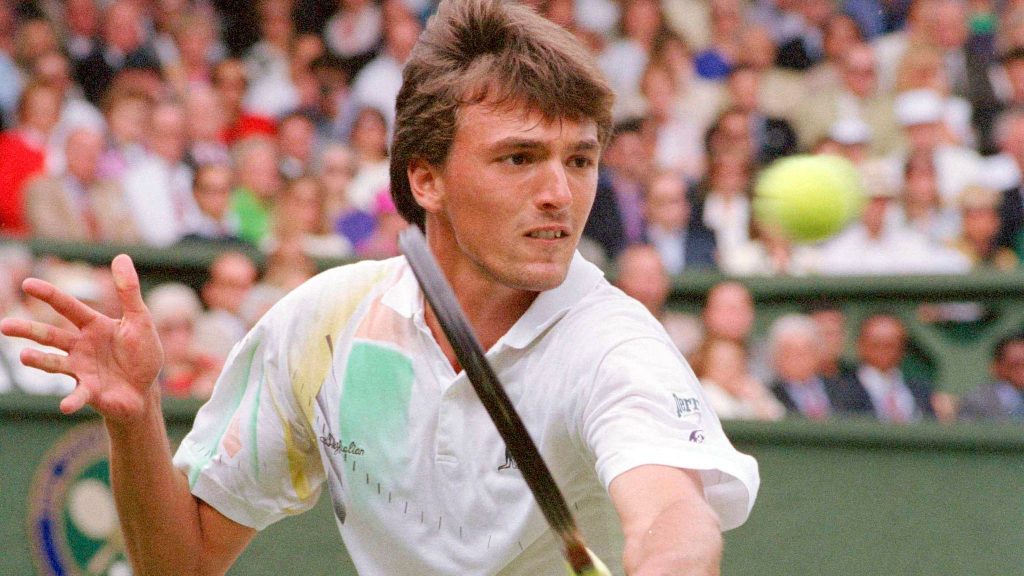

The academy was born

In the 1980s, junior tennis players were training and training hard. The ‘academy’ had been born, Nick Bollettieri’s academy specifically. Some were using Wilson Pro Staff 85’s or the Donnay variant. Some used the Head TXP and its offspring- The Head Prestige Pro 600, Or the Prince Graphite 90. But there was a new breed, training their strokes practicing hard service box drilling and games of topspin angles… with an oversize frame, not an 85sq inch Wilson or 89.5sq inch Head, but a 110 (107) sq inch Prince Graphite.

The frame had shown its capabilities early on, with Michael Chang and Gabriella Sabatini winning Grand Slams. Pat Cash had even won Wimbledon in 1987 with the predecessor to the Prince Original Graphite Oversize, the 1979 Prince Pro Graphite. But change was coming. Michael Chang had won the 1989 French Open title with the POG, becoming the youngest ever male grand slam champion. Chang was a shorter player and predominantly a defensive baseliner, so there is a logic to him using a frame that ‘helped.’

However, baseliners were about to take it to the serve and volleyers like never before, and this was back when courts were still fast, and balls were sometimes heavy. You could argue that the two players, male and female, who changed their respective sports were: Andre Agassi and Monica Seles.

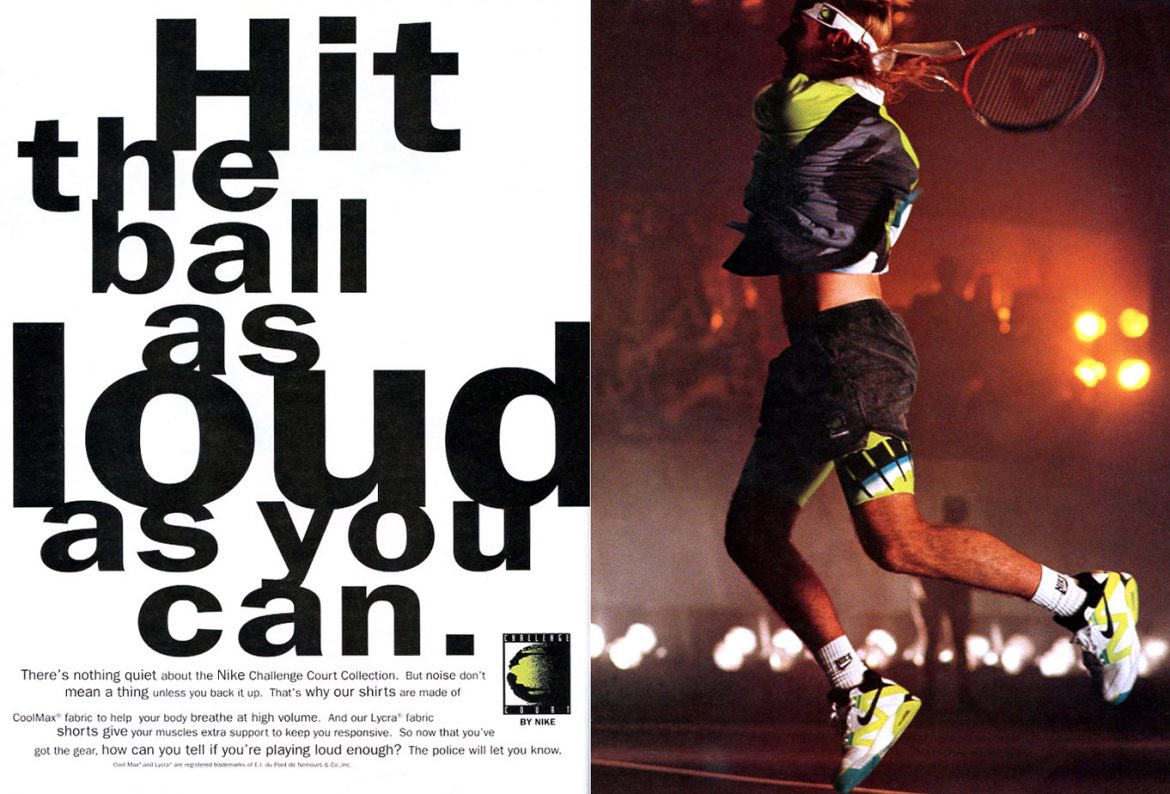

Both used a Prince Graphite Original to develop their aggressive style of baseline play, with both arriving on tour in far from subtle ways, swinging the shiny black Prince frame in anger and attitude as they both launched themselves towards a new horizon.

Imitation is a form of flattery

To be copied or to ‘inspire’ can be seen as a form of flattery. The Prince OG had shown the way, and now tennis had frames ranging from 85sq inch up to 110sq inch as an average rule in pro terms, though there were smaller, and bigger…. incredibly. Sponsorship was becoming a huge business, and one player would go on to change the game like none before.

Flamboyant and in a noise of ‘hair’, lycra and pink Donnay Pro One magnificence Andre Agassi had swept aside every rule of norm on grass to lift the 1992 Wimbledon, beating none other than Becker, McEnroe and Ivanisevic along the way. When you remember that this was the old fast grass, it was astonishing that a baseliner could ever achieve this.

The change had indeed arrived. The route to this in terms of his rackets was somewhat tumultuous and well documented and for many sad reasons, Donnay would fail to gain back its place as the once biggest manufacturer of tennis rackets in the world. I loved the look of that Pro-One so much that I had 5. I hated its flex so much that I broke them all, being the silly petulant and mad teenager I was. Often a man had been waving a shiny black Prince Oversize frame at me as I ranted and raved, but it would be years before I knew why.

Andre’s Donnay, the ‘limited edition mold, was known to be stiffer, such is the way with custom pro-stocks. There is no denying the stark similarity between the frame in Andre’s hands and the original Prince Oversize. ‘Take the torsion bar out, stiffen it up, add some lead and spray it pink for all I care, just make it play like my old Prince!’ you can almost hear someone say. I loved that frame, despite its flaws.

Image is everything

Shortly after his Wimbledon triumph, and in a world of mass media marketing where ‘image was everything’…tennis didn’t just have a new superstar, it had a new megastar with proven Grand Slam credentials. The marketing potential for a ‘new Andre racket’ was enormous, and frankly, Andre needed a new sponsor. Still, as Andre had known, the racket would need to be right, and that is no easy thing to guarantee, never mind patents/intellectual property, making the right ‘recipe’ takes a lot of know-how.

Could anyone make a frame that felt like the Prince he so loved? Yamaha, Mizuno, Yonex and many manufacturers had made oversize frames. Seles had gone to Yonex and straight to number 1. You could even get an oversized Pro Staff Original with a torsion beam. Who could step up to the plate and make or update a frame once visualized and championed by Howard Head?

By a quirk of ironic fate, perhaps, it was the company that still proudly bore his name. Head.

To a tennis nerd, this is where the story gets intriguing, because in the background to all of this, tennis was evolving further still. Wilson had already launched its own ‘update’ with an eye on the future, The Wilson Pro Staff Classic, aka the Wilson 6.1 95. For much of this, I have been showing the two extremes, a small-headed frame with more classical styles of play in general versus the oversize flame-throwing games of new, big-hitting youngsters. But, because they are two opposing poles, it leaves a large gap in the middle, a ‘happy middle ground’ if you like. The place where two extremes meet, but the relevancy of that is only understood when looked at in context of how the game itself, developed and how through necessity, players needed to become more and more complete all-court players.

The happy midplus ground

Head had experimented with ‘mid plus’ frames already, with the Radial tour and its micro-stringing pattern, like an uber dense pattern 96sq inch version of the Prestige Pro 600. Effectively Head had tried to ‘upsize’ the Prestige 600, for reasons known only to them, a different design and layup was needed.

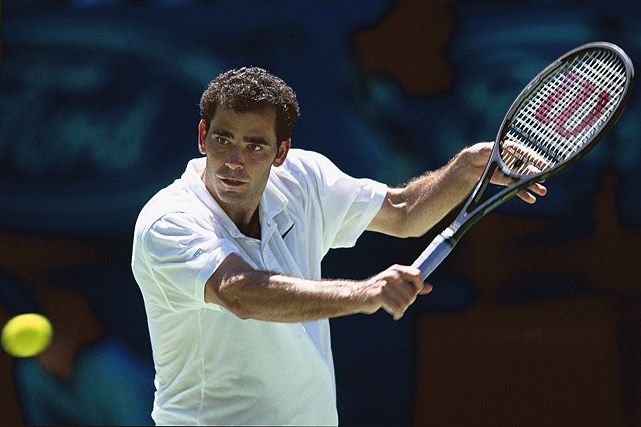

In 1993, the stage was set in the men’s game, with Pete Sampras and Andre Agassi as polar opposites in more ways than just equipment. Agassi was scorching marketing property and Head had an eye on the relevancy of frames for a while, indeed they had probably the most used frame on tour with the Prestige 600, in ‘classic’, ‘tour’ or ‘pro’ versions, but, as a business, you need to forecast what is coming, and to capitalise you need to invest and also gamble.

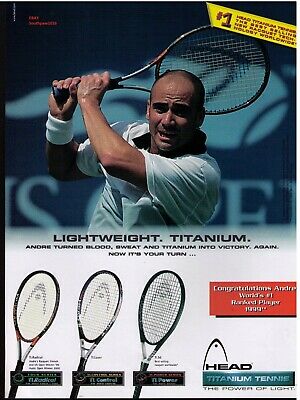

Head had successful names on their books, with Goran Ivanisevic and Thomas Muster spearheading the Prestige line and David Wheaton using the Graphite Tour. Head gambled massively on Agassi, the USA market was phenomenal for tennis gear and the contracts were signed, the potential upside was enormous. But what would the racket be? Would it be any good? Agassi was spotted with the obligatory blacked-out prototypes, media hype and rumors were circling. In 1993, with the fullest force of international marketing fanfare, The Head Radical was born.

The birth of “Radical”

Affectionately known as ‘The Bumblebee’, an oversize 20mm beam (thicker beam than the POG) in-your-face yellow and black frame, with the code PT59. Worldwide it was known as the Head Radical Tour 690, but due to naming issues with the word ‘tour’ at the time, in the USA, the frame was known as the Head Radical Trisys Tour 260 IDS (integrated dampening system). It was that later naming on the frame when Andre went on to win the 1994 US Open title (why I have this version), some said made in Austria, some said designed in Austria, however that was I’m told because Head had opened a specialist paint shop in the Czech Republic, the bare frames were made in Austria but painted in Czech Republic. Either way, a great frame had been made, but not just for the reason of Agassi and all the excitement he bought to the game.

Head had been very clever in their research and development, and business plan. Rather than just gamble on Agassi, they made a second frame mold at the same time, but this one would be a mid plus-sized mold, based off the R&D from the expense put in to the Agassi frame. It slipped a little under the radar at the time, but David Wheaton had immediately switched to this new mid plus-sized frame, the Radical Tour 630.

Players who used a 600 (89.5sq in) racquet, were starting to look at options to move on to, bigger frames, always looking for an upside to their games and so, Head now had a rival mold to Wilson’s growing popular frame, the 6.1 95 classic. Agassi’s PT59 Head Radical Oversize frame, came with a sister. Or should I say, sisters.

The HEAD Pro Tour

I can even remember trying some frames and someone saying to me….no, the blue one, the blue one, as I caressed the lovely claret Prestige Classic 600 in the shop before deciding on the Yellow and Black Agassi frame. ‘The blue one’, seemed to hit the shelves later than the Bumblebee and it sort of flew under the radar, with ‘some guy’ called Muster being the one on the face of the marketing on the frame.

The irony of this little tale is that by the time ‘Guga’ Gustavo Kuerten and his magic blue and black Head frame with the space-age Luxilon strings went and spun everyone off court on the red dirt of Roland Garros in 1997, the frame itself was entering its final period of initial retail sales, though still very much a sideline range in the UK at least to the now established Radical and Prestige lines.

The sister frames that came as a by-product of the PT59 Agassi frame, were coded at the time as ‘PT57’ for the midplus Bumblebee Radical, and at the time PT630 for the midplus Pro Tour, today we know that frame as the PT57A2. Simply, one of the most used frames on the pro-tour. Even to this day there are several players in the top 100 who use that mold, and let’s remind ourselves that the mold is about to also turn 30 years old!

You can trace the lineage, and you could put forwards an argument that without the Prince Oversize, there wouldn’t have been the PT59 Oversize Radical and the dollars behind that opportunity with Agassi as the face of the frame would also have meant that there may never have been the PT57. Still, we may never know that, and perhaps someone in Kennelbach, Austria can correct me on that speculation.

The rivalry of the polar opposites

So, with Andre and Pete, swinging two frames at polar opposites in terms of sheer frame size, the rivalry of the 1990s began. But between those two opposites, with a little help from a leap in string technology, a new dawn was coming. Surely, in a game of top trumps, the winning player would not merely be Sampras or Agassi, but some bionic mix of the two, a great server and also an early ball-striker, great mover, fantastic in both offense and defense, counterpunching, baseline and net play, and surely this player would require a frame that sat somewhere between the 85 and 107 polar ends of the scale?

A man called Roger Federer, of course, came along and tore up that rule book, using a 90 sq inch frame to do all described above in the top trumps, a mere small incremental rise up of frame size over the PS85 and yet set the standard, arguably becoming the ‘father of modern aggressive all-court tennis’.

And then along came Rafael Nadal with his mix of the skill sets, moving on from the Babolat Pure Drive of his youth to a brand-new frame with the word ‘Aero’ in it, launching Rafael and that forehand head first in to the greatest rivalry our sport has known. And again, not an apparent middle ground, this time, another small shift in the extreme poles meant that the next ‘big two’ would have a 90sq inch vs 100sq inch frame rivalry, rather than 85 vs 110.

Rafa could be described as the ‘father of power-spun tennis’ for want of better titles, the frame in Rafas hands, originally titled the Babolat Aero Pro Drive, now known as the Pure Aero, is my nomination for the third game-changing racket of modern times. At club and county level, that frame took players I could previously defeat and turned their games around. With modern strings, I dreaded playing against someone who walked on to the court with one. The game changed. Launch angle, target zones and RPM mattered a lot.

A pattern is emerging here, and it explains how we are where we are today, for we are a product of all that has gone before, usually.

Where are we today?

In 2022, the general retail sales market for aspiring players dictates that the frame will be either 98sq inches or 100sq inches. Some, like Shapovalov, have increased their frame size to 98. Others like Alcaraz have downsized from 100sq inches to 98. It is fair to say I think we have reached, ultimately, that ‘happy middle ground’ I first mentioned, or have we? Take Federer’s 90sq inch frame and Rafa’s 100sq inch frame and find the middle ground and you get…. a 95sq inch frame.

I have read comments where people say that a 95sq inch frame is not suited to ‘the modern game’. Comments to do with the angle that the frame bypasses the ball. All I have to say to that is, the middle of the strings is still the middle of the strings and the contact point is still but a glancing blow. Essentially, if the player is talented enough to middle the ball, it matters less what the frame size is.

The reality is that the game is stretching players in so many ways that the likelihood of that and the necessity for a bit of easier power and depth and more importantly a string bed that responds to ‘off-centre’ off balance strokes is now an important factor in tandem with the way the game progressed with extremities of movement.

The 95 is not dead yet

Roger Federer moved to a 97sq inch frame, past that happy middle ground if you like. A prime example of a player searching for ‘more’ to compete and win as the game progressed. That said, at the time of writing, in 2022, both the men’s world number one and the world number two use a 95 square inch frame. Yes, Daniil Medvedev, his frame is not the retail 98. It is a custom 95, based loosely on a Wilson 6.1 95 from his youth, and as he is in his early 20’s, is he not playing ‘modern tennis’? Is Novak himself not playing ‘modern tennis’. I think that those who lament the death of the 95sq inch frame are a few years premature, but the future can often be spotted via junior ranks, and to defeat the 95’s, players again look for ‘more’.

The 20mm beam 95sq inch frames we have known and loved from both Head and Wilson are no longer available in standard retail shops. Yes, Dunlop still makes a 20mm one, as do Prince and custom companies like Angell. Head make one with a 22mm beam, but that frame started life as the IG Prestige’ S’ I believe, it is not the same. Even the Yonex vCore 95 has changed.

If had asked you to name ‘the most famous 95sq inch frame’, I bet a lot of you would have said the Wilson Pro Staff Classic/6.1 95. It was undoubtedly and an early adopter and is still widely used on tour to this day in one version or another…Del Potro, Evans, Bautista Agut, Opelka, Edmund…. (Medvedev), and has won, I believe 2 grand slam titles on the men’s in Wilson paint since its launch? Was Todd Martin’s frame a Pro Staff 4.2 underneath? I’m not sure.

With history and success mind, getting back to the family lineage, The PT59 came with very important sisters. The PT57’s launched the Radical line, the famous Pro-Tour 630, and you can trace its DNA right through the Prestige MP line, amongst rival manufacturers’ frames too. Head bought subsequent updates and developments throughout the years, not to mention competitors rushing to make their equivalent or alternative. Head, were very, very busy. I made myself a little collection, as you do.

I call it ‘The Class of 95’.

Thanks, Andre

In 1993 with the launch of the POG-inspired Radical Oversize, with Andre Agassi arguably setting the standard and basis for future attacking baseline play, perhaps earning the title of: ‘the father of modern aggressive baseline play’ if I may say. I am biased, can you tell?

In 1993, thanks to Head… ‘Papa really did have a brand-new bat’. Because of that frame, so did countless others, another tale to tell. I nominate the second my second game-changing racquet: The 95sq inch Head PT57.

Thanks, Andre.